A Compass for the Science-Policy Interface

There has been a lot of thought given to the challenge of bridging the “science—policy interface” (or “science-to-policy interface” or SPI) and in some cases there even have been committees formed to function as such (for example, the “UNCCD Science-Policy Interface”). From an academic viewpoint, this is rather remarkable because the definitions for both science and policy vary widely.

What is being interfaced, exactly? Does science include engineering? If engineering is seen as a sub-category of science, then we need to seriously include the “technology—policy interface”. Similar, if economics is considered a science, then we should address the “economics—policy interface” which is a truly confusing idea, given that economics is integral to public policy. And what is the scope of policy? Does it include politics? Again, not trivial, especially if you think internationally. For instance, the word “policy” translated to French reads as “politique publique”, public politics, roughly.

But let’s not pursue this analytical rabbit hole further. The topic has some history behind it. In particular, C.P. Snow’s foundational 1959 Rede Lecture at Cambridge University on “The Two Cultures”. Snow observed that Western intellectual life has become split into two disconnected groups: scientists and literary intellectuals, with “precious little communication between them, little but different kinds of incomprehension and dislike.” Snow was a British physicist who later worked in administration and as a novelist: an integrative thinker.

Professor Marc Saner was the Departmental Science Advisor in the Canadian federal Ministry of Natural Resources from 2022 to 2025, having been seconded from his position as Chair of the Department of Geography, Environment and Geomatics at the University of Ottawa. With a PhD in Ecology and an MA in Philosophy, Marc’s career has spanned not only government and academic science, but also the intersection of the humanities, social and natural sciences. He has brought interdisciplinary perspectives to his work in ethics, risk management, and governance of new technologies in both the public and private sectors. An experienced academic and public sector leader, Marc established a university Institute for Science, Society and Policy, and led nationally recognised programs in evidence synthesis and knowledge translation.

Institute for Science, Society and Policy

University of Ottawa, Canada

I believe Snow’s analysis can be enriched by adding observations from French cyberneticist Joël de Rosnay and Canadian ecologist Buzz Holling. While Snow juxtaposed “scientific vs literary cultures”, de Rosnay differentiated “analytic vs systemic cultures” and Holling, similarly, differentiated “analytical vs integrative cultures”.

An important insight from Holling is that those who take an atomistic or analytical approach in their work, often are able to answer very specific questions well, but these questions (and their answers) may be too fragmented to be relevant in practice. In contrast, those who take a holistic, systemic, or integrative approach may work on the most important and urgent questions, but their answers may be too vague to be helpful in the practice of policy interventions.

A second important insight is that the two cultures may exist within professions, not just between—because there are atomistic vs holistic, as well as theoretical vs applied approaches in most disciplines.

Put all this into the context of science advice for public policy-making. The interplay between an expert advisor and a decision maker is a meeting of two different professions, which is often subject to the cultural differences described by Snow, de Rosnay, and Holling. I spent some time over the years collecting examples of this interplay, some from readings and some from my own workspace (as a scientist, a philosopher, a consultant, a science advisor, and a university administrator).

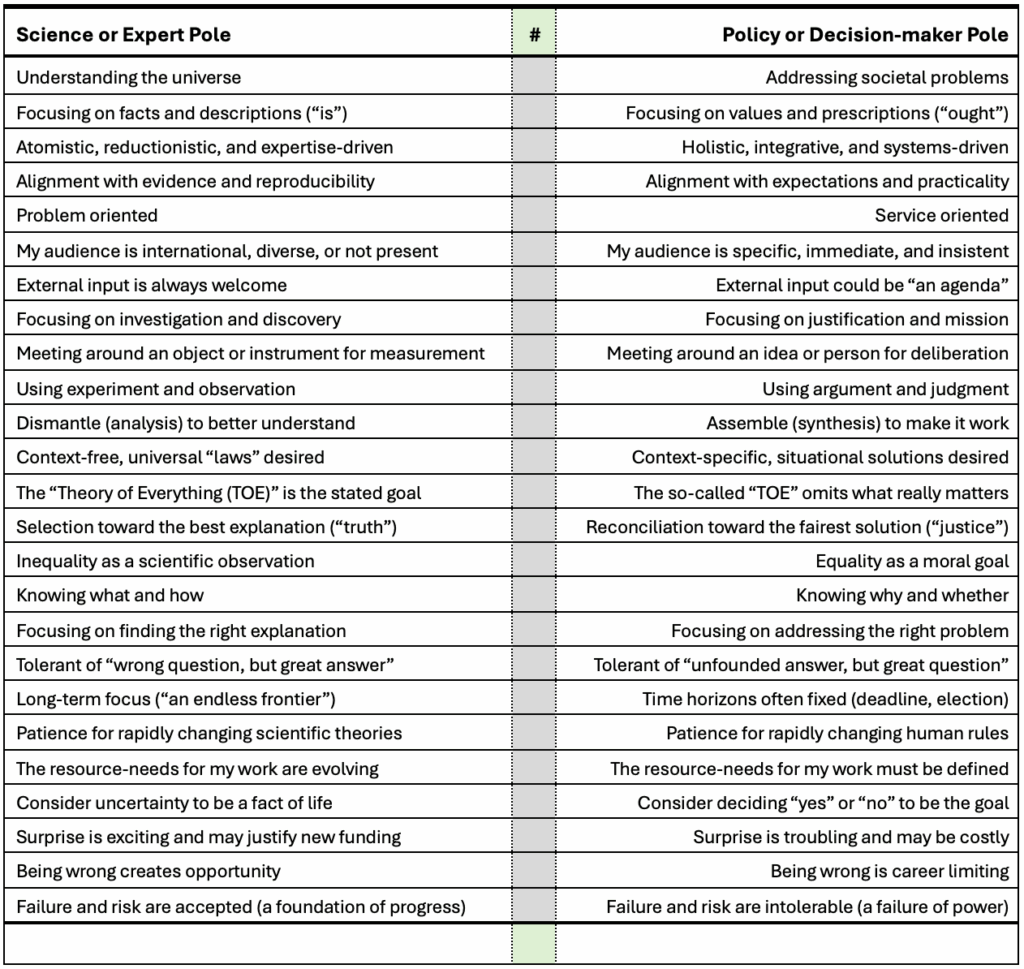

Let me entertain you with a gamified version of this collection. Let’s call it “The Science—Policy Compass” (Table 1).

Table 1 requires two brief disclaimers: First, binaries, stereotypes, and juxtapositions are justifiably criticized as oversimplifications (de Rosnay called his own table a “caricature of reality”), but it is nonetheless useful to describe opposites before we can discuss boundaries and the convergence of cultures. Please select your own favourite metaphor here – Yin and Yang, the Law of Polarity, or thesis-antithesis-synthesis, while you read the statements at the poles.

Second, many self-assessments tools are justifiably criticized for providing unfounded scores (the discredited Myers-Briggs test is an example). Thus, while making no scientific claim, the benefit from going through the 25 rows below is heuristic and self-reflexive. It might illuminate and strengthen your own views on how you can act and communicate best as an agent of collaboration – and that is serious business indeed, even if your score is not.

The Science—Policy Compass

[or alternatively, The Geek-to-Wonk-o-Meter!]

Table 1: You are invited to position yourself on the compass in the following way, by selecting a number and recording it in the grey column.

Select:

1 – if the idea on the left BEST describes you, or how you spend your time

2 – if the idea on the left LARGELY describes you or how you spend your time

3 – if the ideas on both the left and right EQUALLY describe you or how you spend your time

4 – if the idea on the right LARGELY describes you or how you spend your time

5 – if the idea on the right BEST describes you or how you spend your time

Note the sum of the numbers in the bottom row. If the sum is close to 25 (lowest possible) then you may be a “geek”: wear it with pride or call yourself an “expert”. If it is close to 125 (highest possible) then you may be a “wonk”: wear it with pride or call yourself “effective”. At the mean score of 75, you may call yourself “valuable interpreter and broker at the science-policy interface.” Everyone wins …

Full disclosure: my score was 84—but it certainly would have changed over the years.

Despite the obvious difficulty of describing the components and boundaries, the science-policy interface challenges are real. We should not be surprised that scientists and policymakers may find it difficult to communicate and collaborate. At university, the segregation is fostered through the Faculties, from the initiation traditions of undergraduates (“frosh week”) to the bureaucratic procedures that keep faculties and their respective funding siloed.

Any emerging tribal loyalty and competition is tolerated by universities (it was even suggested to me that these socialisation experiences will render alumni more generous after graduation). Diverging worldviews can easily develop; diverging methodologies and jargons are a given. Ideas about the other may be vague or romanticised. For instance, scientists often underestimate the complexity of policy-making and policy-makers often overestimate the precision of science.

‘…scientists often underestimate the complexity of policy-making and policy-makers often overestimate the precision of science…’

When graduates are mixed together again in the workplace, they can be bewildered by other perspectives, skills, jargons, and priorities—and may seek the feeling of belonging that they had at university. Clustering happens either by assignment or by choice and then it becomes helpful to signal belonging to that cluster, even when that signal may undermine broader collaboration.

Add to this the genuine surprise about the non-knowledge of others about a certain theory, book, or author—which is only expanding with the exponential growth of information. It happens all the time even within professions, for example at conferences.

How, then, do we get to communication? By learning the other culture. This can be hard. When I studied biology, the discipline of philosophy was characterized as “naval gazing” by many colleagues. When I later studied philosophy, I was told that I will understand better “once they train the science out” of me (I was also told to “stop making tables”—Table 1 is definitely a relapse). My personal recommendation to anyone who wants to help bridge the interface: learn as much of the other language, concepts, methods and perspectives as you can. Learning to communicate is a responsibility even if it’s a bit of a mystery.

How do we get to collaboration? Begin by moderating any disrespect. Those closer to the decision-making side must never think of scientists and engineers as “little technicians” (I have heard that expression). Never forget that the experts, these “high priests of truth,” have power also. And patience is required because experts may bring many details and sometimes jargon to the table. Anyone can learn science with effort. Trust helps also: a new investment into science may be meaningful for everybody not just the scientists. Our mission requires that we build bridges. Authentic and patient respect really helps to achieve this central goal.

‘…When I later studied philosophy, I was told that I will understand better “once they train the science out” of me (I was also told to “stop making tables”…’

Similarly, those closer to the technical side must never think of communicators, policymakers or politicians as performers who simply proclaim that decisions were “evidence-based” or “evidence-informed” even when they are not. Someone has to lead, which is always difficult, and even more so when evidence is inconclusive or conflicting. If science truly is “an endless frontier” (a slogan suggested by Vannevar Bush to secure long-term funding after WW II in the USA), then it’s also an enterprise where evidence can change and can be doubted. And scientists: please do learn the process, context, and legal constraints—this will often explain how your work can be highly valued, even if you are not asked personally or quoted directly.

When empathy and continuous learning enable mutual respect and trust, then we can collaborate in the middle—and this we must, because we have complex problems that require all sources of knowledge. For most of us, this collaboration is learned in practice, not in theory – and programs of practice can be built and indeed exist, such as Interface, a program initiated by the Chief Scientist of Québec (and INGSA President), Rémi Quirion.

Let us not forget though, that specialization, the division of labor, and the independence of roles are also valuable. Mark Brown, in his 2009 book Science in Democracy astutely formulated this paradox: The more we trust experts, the more we use them in politics, and the more we use them in politics, the less we trust experts.

The final challenge for those of us who function as interpreters, honest brokers and boundary spanners to remain humble, is to find our place, and to avoid forming a tight group practicing “Science Policy”, “Science Diplomacy”, or “Science and Technology Studies” that puts itself on an isolated pedestal as the best tribe yet.

With thanks to Dr Kristiann Allen for constructive insights.

References and Readings

Brockman, J. (1995). The Third Culture: Beyond the Scientific Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster

Brown, M.B. (2009). Science in Democracy: Expertise, Institutions, and Representation. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press

De Rosnay, J. (1975). Le Macroscope : vers une vision globale. Paris: Éditions du Seuil. English translation available here

Funtowicz, S.O & J.R. Ravetz (1993). Science for the post-normal age. Futures 25(7): 739-755, https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-3287(93)90022-L

Holling, C.S. (1998). Two Cultures of Ecology. Conservation Ecology 2(2): 4. Available at http://www.consecol.org/vol2/iss2/art4/

Lee, K. (2012). Compass and Gyroscope: Integrating Science And Politics For The Environment. Washington DC: Island Press

Quirion, Rémi (2024) S’engager à l’interface entre sciences et politiques publiques. Acfas Magazine, 10 octobre 2024. Available at https://www.acfas.ca/publications/magazine/linterface-sciences-politiques

Saner, M. (1999). Two Cultures: Not Unique to Ecology. Conservation Ecology 3(1): r2. Available at http://www.consecol.org/vol3/iss1/resp2/

Snow, C.P. (1956). The Two Cultures. The New Statesman, 6 October 1956. Available at https://www.newstatesman.com/culture/2013/01/c-p-snow-two-cultures

Snow, C.P. (1961). The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution (The 1959 Rede Lecture). New York: Cambridge University Press